The Naturalist and the Neurologist On Charles Darwin and James Crichton-Browne

Stassa Edwards explores Charles Darwin's photography collection, which includes almost forty portraits of mental patients given to him by the neurologist James Crichton-Browne. The study of these photographs, and the related correspondence between the two men, would prove instrumental in the development of The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin's book on the evolution of emotions.

May 28, 2014

James Crichton-Browne, A woman with pursed lips, West Riding Lunatic Asylum, c. 1869 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

It’s a curious thing to think of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) sitting alone, closely studying photographic portraits of the afflicted and insane. But in the late 1860s, that’s exactly what he began doing: he sifted through portraits of kleptomaniacs, nymphomaniacs, sufferers of severe self-importance, hysteria, and general mania. The portraits, nearly forty of them, were a sort of gift from neurologist James Crichton-Browne (1840-1938), who, as director of the West Riding Lunatic Asylum at Wakefield, was a notable figure in neuropsychiatric photography.

Crichton-Browne’s photographs, all half-length portraits, attempted to capture the afflictions of his patients; to record the facial expressions of all sorts of manias for the purposes of scientific observation and diagnosis. The results were a strange kind of family album: a group of now-anonymous patients committed to Crichton-Browne’s care stares blankly into the camera’s lens; their expressions are fixed, their faces twisted into a record of their extreme emotional afflictions. Darwin’s meditations on the photographs—guided by Crichton-Browne’s own observations—had a profound impact on the naturalist’s thinking about the physical manifestations of natural selection.

The two men exchanged letters for nearly six years, trading books and photographs and sharing observations on the anatomy of blushing, the physiology of expression, and the mechanics of hair bristling. Most importantly, the men shared an almost zealous faith in photography’s ability to correct the imperfect observations made by the human eye.

Portrait of James Crichton-Browne featured in the frontispiece to Volume 1 of his The standard physician; a new and practical encyclopaedia of medicine and hygiene especially prepared for the household (1908)- Source.

Though Crichton-Browne and Darwin’s epistolary exchange covered far ranging ground, it seems that Darwin initially contacted the neurologist with a single need. “Sometime ago I went into several shops in London to try to buy photographs of the insane, but failed,” Darwin wrote in a letter dated June 8, 1869.

Like his father, Dr. William Browne—a “medical commissioner in lunacy” and college chum of the famed naturalist—Crichton-Browne was a bit of a medical iconoclast. He advocated for the “moral” treatment of the insane: no restraints, but diversional and occupational therapy with medication as necessary. Crichton-Browne allowed the residents of the West Riding Lunatic Asylum to imbibe on their favorite beer, he organized dances for their entertainment, and he took their photographs. The photographs served two purposes: first, to shock the lunatic out of her affliction by confronting her with her grotesque appearance, and second, to catalog the true look of different kinds of manias and spur specialized care for individual disorders.

James Crichton-Browne, A young bearded man; head and shoulders, West Riding Lunatic Asylum, c. 1869 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

Crichton-Browne eagerly responded to Darwin’s request, providing a handful of photographs but promising more. His portraits joined Darwin’s already expanding collection of photographs, an idiosyncratic collection that the scientist had procured rather haphazardly. Darwin had begun wandering London’s many photography shops as early as 1866, searching out photographs that captured facial expressions. He was hardly discriminating and his collection was far from highbrow: cross-dressed actors, smiling sculptures, stereoscopic prints, amusing collages of dogs and crying babies. It’s the stuff of the nineteenth-century photography market, entertaining curiosities meant to litter the overstuffed chairs of the Victorian drawing room.

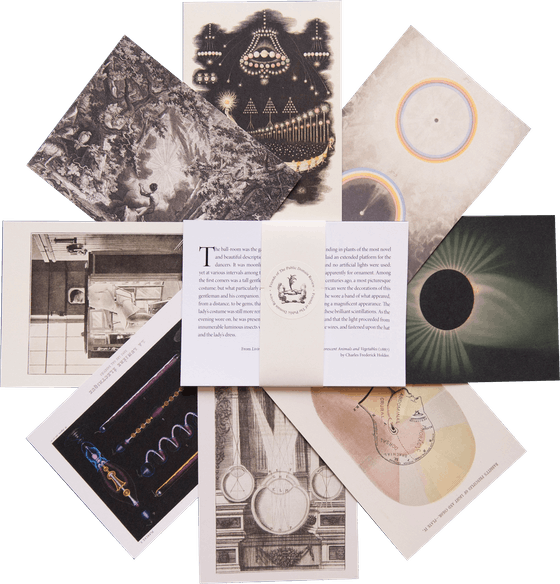

Darwin’s weird and wonderful photography collection was acquired not for parlor games but for the study of human and animal facial expressions. His observations were initially intended as a chapter in his groundbreaking book The Descent of Man (1871). But he found himself so enthralled by the subject that he skipped the chapter and expanded his thoughts into the 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals — widely considered the first English-language scientific text to use photographs.

Multiple Photographers, Illustration of Chapter VII in The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals; Plate II Showing Low Spirits, Anxiety, Grief, Dejection, Despair, c. 1872 — Source.

Expression is the most accessible of Darwin’s books. Far from a dry scientific text, it’s rich with colorful anecdotes drawn from theater, painting and, of course, photography. In it, he argues that man’s emotional expressions—his smiles, snarls, and frowns — are the result of natural selection. If facial communication stems from natural selection, then man must share it with other mammals. “With mankind some expressions, such as bristling the hair under the influence of extreme terror, or the uncovering of the teeth under that furious rage, can hardly be understood,” he wrote, “except on the belief that man once existed in a much lower and animal-like condition.”

T. Wood, Illustration in Chapter V of The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals; Chimpanzee Disappointed and Sulky, c. 1872 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

Darwin’s research for Expression was frustrated by a serious problem: the collection of empirical evidence. Actual facial expressions proved difficult for him to scrutinize at any length; their ephemeral nature frustrated his positivist commitment to observation. In the text, he outlined the many problems that arose from observations of the fallible human eye:

The fleeting nature of some expressions (the changes in the features being often extremely slight); our sympathy being easily aroused when we behold any strong emotion, and our attention thus distracted; our imagination deceiving us, from knowing in a vague manner what to expect, though certainly few of us know what the exact changes in the countenance are; and lastly, even our long familiarity with the subject—from all these causes combined, the observation of Expression is by no means easy.

Photography seemed to be a concrete solution to Darwin’s troubles: a relatively new and neutral technology that he perceived as a simple record, unaffected by demands of aesthetics and artistic interpretation. Photographs also enabled continuous observation of fleeting expressions. He could now observe the discreet flexure of facial muscles, free of “strongly excited sympathy” or “imagination” (both abominable sources of scientific error).

But while photography offered a solution to Darwin’s ills, it introduced another problem, a problem of authenticity. Many of the photographs he found captured what he considered “fake” emotions—emotions that were often enacted rather than felt; strained, no doubt, by long exposure times. This led to inevitable errors of anatomy; a cross-dressed German actor might smile, but he was flexing the wrong muscles to be truly happy. Darwin found photographs of the insane to be the quickest remedy to this problem.

The mentally ill, as Victorian mores held, were emotionally uninhibited and unconstrained. Unable to conform to social norms, the insane were hardly concerned with the suppression of emotion required by the cultured and the sane. To Darwin, Crichton-Browne’s photographs represented something more useful than marketable trinkets. The raw emotion of the inmates at West Riding Lunatic Asylum was primitive, more authentic, and certainly closer to man’s evolutionary ancestors. Crichton-Browne’s project, his interest in capturing the true look of mania, proved a valuable discovery for Darwin.

James Crichton-Browne, Woman Suffering from Chronic Mania, c. 1869 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

James Crichton-Browne, A bald male patient of West Riding Lunatic Asylum, suffering from “Mono-mania of pride,” c. 1869 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

Darwin found in Crichton-Browne a fellow scientist sympathetic to his theories and ready to expound on his observations. The correspondence between the two men is colorful, replete with vignettes from Crichton-Browne’s blushing sister-in-law to the “observed hilarity” of women “labouring under erotomania, nymphomania, or any disorder of the sexual propensities” (Letter from JCB to CD, February, 16 1871). Though Crichton-Browne refers to very few of his photographs specifically, his letters flesh out the otherwise vacant personalities captured by his camera. In a single letter, he describes the “hilarity” of sexually perverse women; the “remarkable lachrymal secretion” of “melancholics, who sit rocking themselves rhythmically backwards and forwards”; and “a stereotyped smile” of “many idiots and imbeciles who are constantly smiling and laughing, who are `pleas[ed] with a rattle, tickled by a straw.’”

The naturalist was eager to solicit Crichton-Browne’s observations on the mechanisms of expression as well as his opinions on the most recent literature on the subject. Darwin forwarded his large volume of Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne’s 1862 book, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, ou analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions. Duchenne, a physician at the famous Parisian asylum Salpêtrière, had discovered that by using electric probes, he could cause isolated groups of muscles to contract and artificially induce facial expressions in his subjects. Lavishly illustrated with numerous photographic plates demonstrating Duchenne’s grotesque-looking experiments, Mécanisme, was invaluable to Darwin’s research. He and Crichton-Browne exchanged the volume many times throughout their correspondence; Darwin’s copy of the book — now housed at the Darwin Archives at Cambridge University — is filled with their questions and annotations, scribbled in its margins.

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne, Duchenne Performing Facial Electrostimulus Experiments; Showing “Terror,” c. 1862 — Source.

Darwin seemed to have been most interested in discreet effects of mania on the body. Crichton-Browne, no casual witness of emotional extremities, wrote detailed descriptions of his patients’ attacks, listing every fiber of musculature that flexed in the action. In a March 15, 1870, letter, Crichton-Brown describes a woman from Huddersfield who:

Believes that her head is burnt & that there is not a drop of blood in her body. She has an agonized expression. There is marked elevation of the outter [sic] third of the left eyebrow, the skin of the forehead over it being gathered into a multitude of minute wrinkles; the corresponding part of the right eyebrow depressed & overhanging. The corrugatores superciliorum, powerfully contracted. The eyeballs much exposed, the upper eyelids having an abrupt angular arch rather to the inside of their central points; a rounded kite-shaped fullness over the upper lid: angles of the mouth pulled down; constant restless movements, rubbing & wringing of the hands, with twisting of the body from side to side, the neck being held rigid as if apprehensions were entertained as to any movement of the head.

I have read your remarks on blushing to my sister in-law, one of the best or worst blushers I ever encountered— a young lady very sanguine & sensitive and she pronounces them strictly correct. She says that when blushing she often stammers and does not know what she is saying. I suggestd [sic] to her that this was due to a feeling of increased awkwardness knowing that her blushing was observed—but she says, No because she has felt quite as stupid when blushing at a thought in her own room. I can make this young lady blush at any moment by looking at her intently.

A good portion of their correspondence is dedicated to the effects of emotional distress on the hair. Darwin was particularly interested in establishing a link between the bristling hair of unsettled lower primates and humans. In Expression he compared raised hairs on anthropoid apes and on the nape of a canine neck — both of which occurred only when the animals were agitated. Convinced of the truthfulness of the old adage “hair raising,” Darwin plied Crichton-Browne for his own reflections. On June 1, 1869, Crichton-Browne wrote:

With reference to the erection of the hair in acute melancholia & hypochondriasis. There is in both these conditions, a persistent state of painful emotion (either terror or anxiety) varied by paroxysms of more intense suffering. It is in these paroxysms that the bristling of the hair is most frequently noticed . . . It is attributable . . . partly to the sub-acute emotional perturbation . . . which creates a tendency to certain actions & modes of action, & which is operative I am satisfied even upon the hairs.

The wife of a medical man, with whom, a patient of mine a lady suffering from acute melancholia, (characterized by convictions of unpardonable sin, fear of death for herself her husband & her children), said to me the other day, without the faintest suggestion on my part,— “I think Mrs. H. is going to begin to improve because her hair is beginning to get smoother. I always notice that our patients” (a considerable number of lunatics have resided with the speaker) “begin to get better whenever their hair ceases to be rough & untidy & unmanageable” This is a curious empirical observation.

Their exchange on the subject of bristling hair continued for nearly a year. On June 6, 1870, Crichton-Browne sent Darwin a photograph of a “female patient . . . in whom the bristling of the hair was well seen. The woman was in a tranquil mood when the portrait was taken. When she was agitated—the ascendant emotion being horror—the hair stood out like wire.” The accompanying photograph of a placid-faced woman with possibly ethnic hair was the only one of Crichton-Browne’s portraits to appear in Expression, though it was reproduced as a wood engraving.

James Davis Cooper after a James Crichton-Browne photograph, Illustration from Chapter XIII of The Expression of the Emotions of Man and Animals; Insane Woman Showing the Condition of Her Hair, c. 1871-1872 — Source: Wellcome Library, London.

It is, perhaps, a bit surprising that despite Darwin’s direct solicitation of both Crichton-Browne’s photographs and observations that only one of his portraits was reproduced in Expression. But despite the limited use of Crichton-Browne’s photographs, Darwin found his insights invaluable. Darwin wrote the neurologist in March of 1871 and suggested to him that he should be credited as co-author of Expression. Crichton-Browne politely declined.

Darwin’s commitment to typicality — the scientific median — was often at odds with Crichton-Browne’s interest in the abnormality of affliction. In addition to his asylum portraits, the neurologist had forwarded Darwin photographs of a family of “imbeciles” committed to an asylum in Scotland, photographs of grotesquely disfigured patients, and a photograph of a child that the neurologist described as a “Yorkshire cretin.”

Stassa Edwards is a writer and editor. Her writing has appeared in numerous outlets, including Lapham's Quarterly, Aeon, Cabinet, Dwell, and Slate.