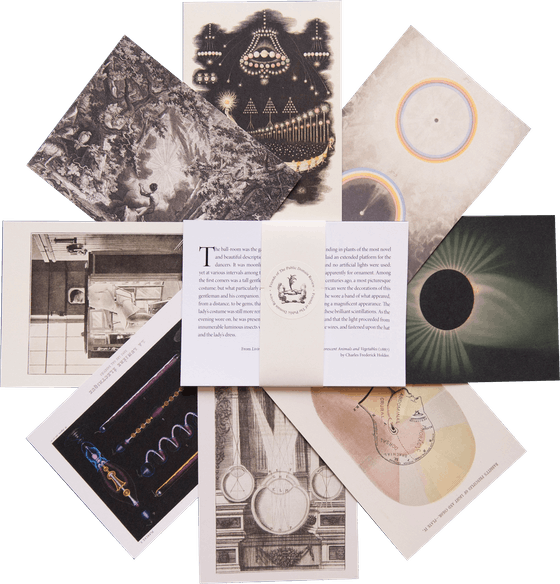

[notes toward] The Encyclopedia of Light

All writing elides, to a greater or lesser degree, the way it came to be what you read. How many times did I start that last sentence? Five times. But four of them are no more. Had I penned those words in ink, however, scribbling away on a sheet of paper, traces of each false start would remain, and you would see my thinking in a way that, reading me now, you do not. Composition in digital media has, in this way, made for a special kind of frictionless world of sublated erasures, deleted deletions, and endless, invisible recompositions. In the affecting work of sensory history that follows, Peter Schmidt uses the “strikethrough” as a kind of shadow-writing: his “Encyclopedia of Light” reveals little dark threads of undoing — marks of the second thought that endlessly cancels the first. We write, now, of course, with light, looking at glowing screens. But it is a strangeness of our monitors that we erase what we have written with still more light: a blinking cursor, backing over the words. What is Goethe supposed to have said upon his deathbed? Mehr Licht! More light! And he was erased. What follows, too, reaches for light — but the light will not be grasped.

— D. Graham Burnett, Series Editor

April 13, 2022

An anonymous observer in the Vaisheshika, India’s ancient school of Vedic philosophy, asserted in the sixth century BC that light and heat are “one substance” of two types: latent (seen) and manifest (felt). “Fire is both seen and felt. The heat of hot water is felt but not seen; moon shine is seen but not felt. The visual ray is neither seen nor felt.”

The centuries-long debate over light’s source—eye or object?—was settled by Moorish mathematician Ibn al-Haytham (965-1040). al-Haytham reasoned that, if it pains one’s eyes to behold the sun, then sunlight cannot possibly originate in the eyes, and must therefore be imparted by the object of vision itself. He conducted his research in the near-darkness of a mausoleum near Cairo’s al-Azhar mosque…

Early evening. Between the suspension cables flickering past the train window, a satin-soft purple glow. I make a point to look out of the window when crossing the bridge. To see so many lives through one pane reminds me that my reality is just one of an uncountable many. Often this thought saddens me, but today it comes as a relief.

The cyanometer (/saɪ əˈnɒm ɪ tər/) is an instrument for measuring “blueness” attributed to naturalists and explorers Alexander Humboldt and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. The device comprises squares of paper dyed in graduated shades of blue which can be held up and compared to the color of the sky. De Saussure's cyanometer had 53 sections…

In one work, Isaac Newton (1643-1727) schematized the constituent wavelengths of white light by matching each spectral color to a range of frequencies on the musical scale: purple (G-a), indigo (a-b flat), blue (b flat-c), green (c-d), yellow (d-e), orange (e-f) and red (f-g). According to Newton’s device, any visible wavelength has its corresponding musical tone…

In his Theory of Colors, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) asserted that each of light’s spectral colors were naturally generative of a particular mood. Yellow produces “a serene, gay, softly exciting character”; blue, “a kind of contradiction between excitement and repose…” In Goethe’s view, to every quality of light there corresponds a distinct emotional temperament…

I imagine sometimes, that when the ocean has swallowed the coasts and the forests have burned, I will look up to find a lavender glow hanging above me, and recall having seen this very same light before, and when it was, and where, and permit myself the comforting, if fleeting notion, that maybe not so much has changed.

Radiative forcing is the variation in the energy flux of the atmosphere resulting from the interaction of sunlight, the earth’s surface and natural and anthropogenic particulates… Estimates suggest that the total amount of solar energy trapped by greenhouse gases since 1998 is equivalent to more than 3.1 billion of the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima…

Inspired by the deep blue glaciers of the western Alps, John Tyndall set out to understand the relationship between aerosols and the mystifying blueness of the sky. His experiments filling a glass cylinder with mixtures of various gases, including carbon dioxide, benzene and butyl nitrite, and illuminating them with a beam of light, produced a variety of celestial blue clouds. The result of his experiment, he wrote, “rivals, if it does not transcend, that of the deepest and purest Italian sky.”

Tyndall’s colleague, philosopher John Ruskin, praised Tyndall’s creating “within an experimental tube, a bit of more perfect sky than the sky itself.” Yet on the same day Ruskin wrote in a letter to a friend: “I’ll thank them—the men of science—and so will a wiser future world—if they’ll return to old magic—and let the sky out of the bottle again, and cork the devil in…”

Past midnight. Rather than going back to sleep, I open the sliding door, step onto the terrace and gasp. The cold is unexpected, almost inconceivable. The city is a dull sodium-orange smolder against the low dark clouds. I can look for only so long. Back in bed, I warm my stiff fingers between my thighs and feel my heart hammering against my ribs. Eventually, I cannot help but laugh at my body’s alarm. As if this were the first time I had felt the cold.

The proposed operation would spray calcium carbonate (CaCO3) aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight and cool the planet. Models suggest that these particulates would change the color of blue skies to a cloudy white. Beyond that, however, the project’s directors concede that they cannot predict what effects this solar geo-engineering would have on the earth’s climate…

Peter Schmidt is a writer, researcher and founding member of the Global Experimental Historiography Collective. His novel, A Mountain There, is forthcoming. He lives in New York City.

![[*Door creaks open. Footsteps*]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on *Aesthetic Theory*](https://the-public-domain-review.imgix.net/essays/mimesis-expression-construction/5448914830_cc288c2266_o.jpg?w=600&h=1200&auto=format,compress)

[Door creaks open. Footsteps]: Fredric Jameson’s Seminar on Aesthetic Theory

By meticulously translating his recordings of Jameson’s seminars into the theatrical idiom of the stage script, Octavian Esanu asks, playfully and tenderly, if we can see pedagogy as performance? Teaching and learning, about art — as a work of art? more

Chaos Bewitched: Moby-Dick and AI

Eigil zu Tage-Ravn asks a GTP-3-driven AI system for help in the interpretation of a key scene in Moby-Dick (1851). Do androids dream of electric whales? more

Concrete Poetry: Thomas Edison and the Almost-Built World

The architect and historian Anthony Acciavatti uses a real (but mostly forgotten) patent to conjure a world that could have been. more

Brad Fox tells a history-story that pulls on a life-thread in the tangle of things. But that only makes it all a little knottier, no? more

A second life? To live again? Fyodor Dostoevsky survived the uncanny pantomime of his own execution to be “reborn into a new form”. Here Alex Christofi gives these very words a kind of second life, stitching primary source excerpts into a “reconstructed memoir” — the memoir that Dostoevsky himself never wrote. more

In this affecting photo-essay, Federica Soletta invites us to sit with her awhile on the American porch. more

.jpg?w=600&h=1200&auto=format,compress)

At the intersection of surfing and medieval cathedrals, from the contents of a suitcase, Melissa McCarthy stages a plot that walks its way across paranoia, language, and the pursuit of knowledge. more

Food Pasts, Food Futures: The Culinary History of COVID-19

A criti-fictional course-syllabus from the year 2070 — a bibliographical meteor from the other side of a “Remote Revolution”. more

Titiba and the Invention of the Unknown

In this lyrical essay on a difficult and painful topic, the poet Kathryn Nuernberger works to defy history’s commitment to distance, to unsettling effect. more

In Praise of Halvings: Hidden Histories of Japan Excavated by Dr D. Fenberger

Roger McDonald on the mysterious Dr Daniel Fenberger and his investigations into an archive known as “The Book of Halved Things". more

Weaving extracts from a naturalist’s private journals and unpublished sci-fi tale, Elaine Ayers creates a single story of loneliness and scientific longing. more

Remembering Roy Gold, Who was Not Excessively Interested in Books

Nicholas Jeeves takes us on a turn through a Borgesian library of defacements. more

Kant in Sumatra? The Third Critique and the cosmologies of Melanesia? Justin E. H. Smith with an intricate tale of old texts lost and recovered, and the strange worlds revealed in a typesetter's error. more

Lover of the Strange, Sympathizer of the Rude, Barbarianologist of the Farthest Peripheries

Winnie Wong brings us a short biography of the Chinese curioso Pan Youxun (1745-1780). At issue? Hubris, hegemony, and global art history. more

The Elizabeths: Elemental Historians

Carla Nappi conjures a dreamscape from four archival fragments — four oblique references to women named “Elizabeth” who lived on the watershed of the 16th and 17th centuries. more

Dominic Pettman, through the voice of a distant descendant of the Roomba, offers a glimpse into the historiographical revenge of our enslaved devices. more

Every Society Invents the Failed Utopia it Deserves

In a late 19th-century anarchist newspaper, John Tresch uncovers an unusual piece, purported to be from the pen of Louise Michel, telling of a cross-dressing revolutionary unhinged at the helm of some kind of sociopolitical astrolabe. more

In Search of the Third Bird: Kenneth Morris and the Three Unusual Arts

Easter McCraney explores the ornithological intrigues lurking in an early-20th-century Theosophical journal. more