Inside the Empty House Sherlock Holmes, For King and Country

As a new series of BBC’s Sherlock revives the great detective after his apparent death, Andrew Glazzard investigates the domestic and imperial subterfuge beneath the surface of Sherlock Holmes’s 1903 return to Baker Street in Conan Doyle’s ‘The Empty House’.

January 8, 2014

Detail from a Sydney Paget illustration to ‘The Final Problem’ which appeared in The Strand Magazine in December, 1893. Holmes and Moriarty tussle over Reichenbach Falls before Holmes falls to his apparent death — Source.

Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes saga has enjoyed -- or in some cases suffered — countless reinventions since its original publication from 1887 to 1927. The BBC’s current television version starring Benedict Cumberbatch is perhaps one of the most successful, not least as its scriptwriters combine a deep knowledge of the original with a flair for departing wittily from it: the show’s strategy of allusion, transformation, and up-to-dateness gives it both freshness and familiarity. The new series begins with ‘The Empty Hearse’, its title alluding playfully to Conan Doyle’s 1903 story ‘The Empty House’ in which Holmes returns from apparent death at the hands of Professor Moriarty in Switzerland.

Conan Doyle’s saga is particularly suited to this kind of treatment: the fan-critics who call themselves “Sherlockians” pore over the details of Dr John Watson’s narratives (known in the trade as “the Canon”), looking for clues, contradictions, and anomalies; they construct often conspiratorial alternative explanations of events, uncover Conan Doyle’s (or Watson’s) apparent errors, and cross-reference the stories with encyclopaedic scholarship. So, while Conan Doyle is often seen as a fairly transparent writer, eschewing complexity, technical innovation, and challenges to orthodox ideology in favour of elegant myth-making, the industriousness of the Sherlockians shows that the simplicity of these stories is often deceptive: in a story such as ‘The Empty House’, a great deal of important information is left unsaid or hinted at. Recovering those subtexts through careful reading and a knowledge of what else was going on at the time can help to show Holmes and his creator in a new light.

‘The Empty House’ weaves together two narratives, a murder mystery and the story of Holmes’s return to London, three years after his apparent death in Switzerland in 1891. Reunited with his old friend and chronicler Dr Watson, Holmes recounts the story of his escape at the Reichenbach Falls followed by an extraordinary and exotic odyssey:

I travelled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhassa, and spending some days with the head lama. You may have read of the remarkable explorations of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend. I then passed through Persia, looked in at Mecca, and paid a short but interesting visit to the Khalifa at Khartoum the results of which I have communicated to the Foreign Office.

These three sentences contain a wealth of allusions to imperial exploration and conquest. ‘Sigerson’ is perhaps an allusion to the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, whose groundbreaking explorations of Central Asia and the Tibetan plateau — his findings first published in a British and American edition in 1903 — had begun to excite interest and admiration. But it was another explorer of Tibet who was really making the headlines, and which alerts us to the imperialist sub-text of the story. By 1903, Francis Younghusband’s “expedition” to Tibet was in full swing. He entered the country in December 1903 with a force of 10,000 and reached Lhasa in August 1904: it was an invasion in all but name, the final episode in what Kipling dubbed “the Great Game” in which Britain and Russia fought a cold war for control of the Asian lands that lay between their two empires. Holmes’s presence in Lhasa in the 1890s disguised as Sigerson was more likely to be read as groundwork for Younghusband’s invasion than disinterested exploration or an extreme method of lying low.

Detail of a photograph from Perceval Landon’s The Opening of Tibet (1905) showing Chinese representatives in Lhasa meeting Colonel Younghusband in 1904 for the first time — Source.

A “Great Game” explanation may lie behind Holmes’s time in Persia, another object of intense Anglo-Russian competition: Russia’s increasing economic involvement with the Shah’s regime at the turn of the century was viewed with alarm in Whitehall and Calcutta as a threat to the frontiers of British India. Mecca, the next port of call, would have required Holmes (who presumably had not converted to Islam) to adopt one of his famous disguises, as the British explorer and diplomat Sir Richard Burton had done during his expedition in 1853. And Holmes’s talent for disguise would most certainly have been required at his next destination: as he makes clear, Khartoum (or more strictly the neighbouring city of Omdurman) was in the 1890s under the control of ‘Abdallahi, the Khalifa, successor to Mohammed Ahmed, the Mahdi.

The Khalifa and his state in the Sudan, the Mahdiyya, held a similar position in the late-Victorian consciousness as the Taliban and Al Qaida do today. The Mahdiyya’s forces had been responsible for some of Britain’s most disastrous military defeats of the 1880s, leading eventually to the martyrdom of General Charles Gordon, whose portrait, we are told in ‘The Adventure of the Cardboard Box’, hangs in 221b Baker Street. In 1897 Conan Doyle was accredited as a journalist for the Westminster Gazette to accompany Herbert Kitchener’s expedition into the Sudan to wipe out the Mahdiyya, although his journalism was not much of a success as he was instructed by Kitchener personally to go home. Nevertheless, Conan Doyle’s dispatches for his newspaper reveal an enthusiastic support for Kitchener’s project which climaxed in 1898 with the Battle of Omdurman, in which 10,000 of the Khalifa’s forces were killed in a matter of hours by the British and Egyptian armies (which themselves suffered a mere 47 fatalities).

Detail from an 1898 painting by Richard Caton Woodville showing the slaughter of the Khalifa forces at the Battle of Omdurman — Source.

In ‘The Empty House’, then, Conan Doyle writes of the period before Omdurman but with the knowledge of its outcome. Holmes’s casual reference to communicating with the Foreign Office only seems to confirm what has already been signaled: he has spent the three years after his escape at Reichenbach not merely hiding from Moriarty’s henchmen, but working clandestinely for the British Empire.

Holmes returns to London to solve the murder of the Hon. Ronald Adair, a ‘locked room mystery’ in which a young aristocrat is found shot dead in his upstairs sitting room, locked from the inside, at 427 Park Lane. The window is open but there are no signs that anyone could have entered through it; there is no weapon, but on the table next to Adair are piles of gold and silver coins, some banknotes, and a sheet of paper bearing names and numbers. We are told that Adair spent most of his time playing cards in various London clubs, and the names on the paper are of fellow card players. We are also told that his engagement to his fiancée has just been broken off, and that he and his friend Colonel Sebastian Moran had recently won a large sum at cards from Godfrey Milner and Lord Balmoral.

Holmes’s prior knowledge appears to solve the mystery. He knows that Col. Moran is in fact one of Professor Moriarty’s henchmen and “the second most dangerous man in London”. He traps Moran by placing a wax dummy (moved at intervals by Mrs Hudson) in the window of his rooms in Baker Street; he, Watson and Inspector Lestrade look on as Moran takes his position in an empty house with a line of sight to the window, aims his German-made air-rifle adapted to take soft-nosed bullets, and shoots the wax dummy. Lestrade arrests Moran as the murderer of Ronald Adair.

The identity of Adair’s murderer signals another aspect of the story’s imperial sub-text. Col. Moran has entered the worlds of elite leisure (high-class gambling) and elite crime (Moriarty’s gang) from a background in Her Majesty’s Indian Army where he was, Holmes reveals, “the best heavy-game shot that our Eastern Empire has ever produced”, famous for stalking tigers in the jungle: Holmes calls him an “old shikari” — an Urdu word for hunter. Like Watson, he has served in Afghanistan (unlike Watson, with such distinction as to be mentioned in despatches), and he has empire in the blood: his father was a former British Minister to Persia. Watson is astonished by this renegade’s background as an “honourable soldier”, prompting Holmes to speculate that Moran’s “sudden turn” to evil is the result of some inherited genetic marker.

There are many intriguing subtexts in this mystery — anxiety about the implications of Germany’s technological preeminence, fashionable theories of degeneration — but the one to concern us here is Moran’s immaculate army record. This story is in part an enquiry into how and why initially decent men of empire might become bad apples. Some clues within the text suggest that Conan Doyle had an actual case in mind. Asked by Watson for Moran’s motive in killing Adair, Holmes’s answer hinges on speculation that Moran was cheating at cards and that this had been discovered by Adair: “Very likely he had spoken to [Moran] privately, and had threatened to expose him unless he voluntarily resigned his membership of the club, and promised not to play cards again.” Rather than give such an undertaking, Holmes hypothesizes, Moran murdered Adair.

Here the story appears to be alluding to one of the biggest aristocratic scandals of the previous decade. What was known as “the Baccarat Scandal” or “the Tranby Croft affair” had obsessed the Victorian newspaper-reading public when it came to the High Court in 1891. A Lieutenant-Colonel in the Scots Guards, Sir William Gordon-Cumming, had been accused of cheating at baccarat — a variation of pontoon or vingt-et-un with a banker, two players, and two groups of observers betting on whose hand is closest to nine — by his hosts and some fellow former army officers during an aristocratic party at Tranby Croft in Yorkshire in September 1890. Gordon-Cumming, a baronet and major Scottish landowner who had fought with great distinction in the Zulu War, and the Egyptian and Sudanese Campaigns (including at the battle of Abu Klea in 1884 as part of the doomed mission to relieve General Gordon at Khartoum), and who was an admired hunter of Indian tigers, sued his accusers for slander and lost. What elevated this from the ordinary was the identity of the banker during two evenings of baccarat and who had to take the stand in the witness box at the High Court: Albert Edward, Prince of Wales who, after his mother’s death in 1901, became King Edward VII and Emperor of India.

Edward was well-known for his indiscretions — not for nothing did Henry James christen him “Edward the Caresser” — but being called as a witness meant that that he enjoyed the dubious distinction of the first heir to the throne to do so under sub poena since the man who became Henry V was prosecuted in 1411. This scandal was, therefore, one of Edward’s most serious, revealing him as an habitual player of an illegal game. It could have been worse for Edward: the parties to the case and their legal representatives agreed not to mention in court the inconvenient fact that Edward travelled around the country with his own set of baccarat tokens.

L’enfant terrible: Caricature from the satirical magazine Puck from June 1891. On the occasion of his participation in gambling Queen Victoria shows the Prince the list of his misdemeanours — Source.

The Victorian press, cramming the packed court, examined every detail of the case. Gordon-Cumming’s words and actions on two evenings in 1890 became national news, including the question of whether a sheet of paper on which he recorded the progress of each hand had facilitated his cheating or was evidence to support his innocence. But the key events came after some of the other players observed Gordon-Cumming apparently (and in the rules of the game illegally) raising or lowering his stakes in accordance with the turn of the cards. Gordon-Cumming was confronted, but denied cheating: the matter was passed to the most senior guest present. Edward’s judgment was that the whole thing should be brushed under the carpet, but to preserve everyone’s sense of justice, Gordon-Cumming would be required to sign a statement vowing never to play cards again. Edward hoped that the matter would end there, but months afterwards, rumours began to circulate, and Gordon-Cumming felt he had no option but to sue. After his defeat, he was ostracized by Edward and the royal courtiers, so he married an heiress and retired to his gloomy estate at Gordonstoun in Scotland. The popular verdict, though, appears to have been that he was an innocent man unjustly slandered, and more recent enquiries suggest that the accusation of cheating was revenge from fellow-guests fed up at his success in seducing their wives.

Another hint of the Tranby Croft Scandal lies in the name of Moran and Adair’s card-playing associate, Lord Balmoral. No commoner would be allowed to take a title from the Royal Family’s castle in Aberdeenshire. Edward VII would have been much in most people’s minds as he had only been crowned King-Emperor in August 1902, but particularly in Conan Doyle’s: the author had been placed next to Edward at a dinner a few weeks before, and was knighted by Edward in October. Conan Doyle liked Edward, and predicted that his reign would be far more successful than his many critics had suggested.

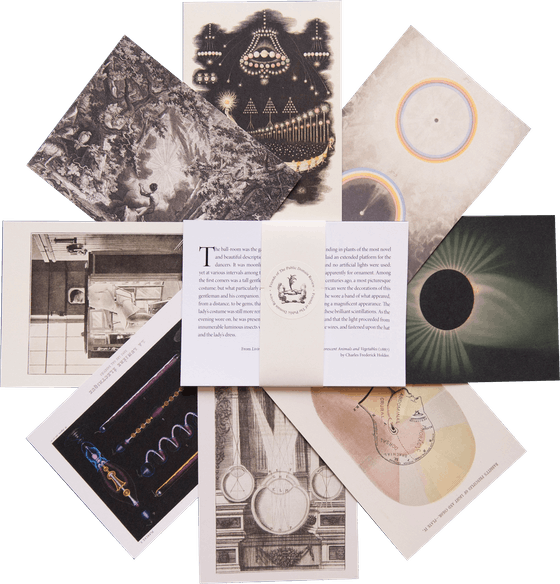

The cast of players involved in the Royal Baccarat Scandal. Photo taken at Tranby Croft, the country home of Sir Arthur Wilson. Among those pictured are: Sir William Gordon-Cumming (1848–1930); Lycett Green and his wife: Capt. Berkeley Levett of the Scots Guards; Sir Arthur Wilson and Mrs. Wilson; Lord Coventry; Lord Somerset; and HRH Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII of England — Source.

Lt. Col. Gordon-Cumming, the war-hero and big-game hunter who (allegedly) cheated at cards and was forced to sign a statement following his exposure, seems a likely candidate for Col. Moran who kills rather than sues his accusers. At this point, the problem of the corruption of honourable empire men would seem to be solved: they are bad apples who, in the end, get found out and punished. Another possible allusion, however, complicates matters. Ronald Adair’s mysterious sheet of paper recalls Gordon-Cumming’s which was the focus of so much attention in court, inviting us to consider whether there is something of Gordon-Cumming in Adair as well. And there are other suggestions that Adair — who also has empire in the blood, as his father was a former governor of an Australian colony -- is not the innocent victim of Holmes’s convenient explanation.

Indeed, Holmes’s explanation is not only preposterous but also inadequate in explaining the many tantalizing details at the scene of the crime and in Adair’s personal history. Why did his fiancée break off their engagement? Why did Adair lock the sitting-room door (a detail to which our attention is drawn but which is left hanging)? Most importantly, perhaps, Adair is (like Edward VII) an habitual gambler, “playing continually”, and for money: this idle, moneyed, gambling-addicted bachelor is not the stuff of which empires are made. Holmes’s inability to come up with a credible motive for the murder of Adair forces us to conclude that his partnership with Moran was a partnership in crime that had gone sour.

What then do we make of Holmes’s apparent determination to cover things up? At Tranby Croft Edward had acted as judge and jury, effectively condemning Lt. Col. Gordon-Cumming so that aristocratic codes of form could be preserved and the secrets of the high-life could remain concealed. In exonerating Adair, and pinning all the blame on Col. Moran, Holmes constructs a convenient fiction to preserve the myth that honourable men remain honourable in all but the most rare and exceptional cases. Holmes, the clandestine imperial warrior, had come home to shore up an aristocracy (and in real-life a royalty) that was vulnerable to allegations of impropriety. No wonder that we learn in ‘The Adventure of the Three Garridebs’ that Holmes was offered — and unlike his creator refused — a knighthood in June 1902 “for services which may perhaps some day be described.”

Andrew Glazzard recently completed a doctorate in English literature at the University of London. He has written on Joseph Conrad, H.G. Wells, and Arthur Conan Doyle, and is currently writing a book on Conrad and popular fiction.