Divine Comedy Lucian Versus The Gods

With the twenty-six short comic dialogues that made up Dialogues of the Gods, the 2nd-century writer Lucian of Samosata took the popular images of the Greek gods and redrew them as greedy, sex-obsessed, power-mad despots. Nicholas Jeeves, editor of a new edition for PDR Press, explores the story behind the work and its reception in the English-speaking world.

March 23, 2016

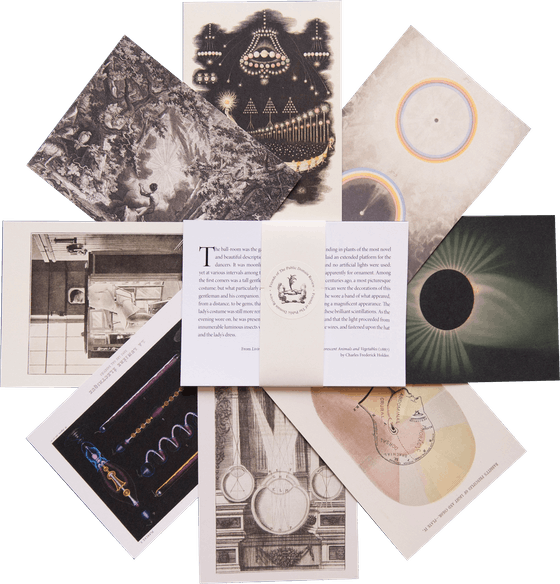

Image of Lucian appearing on the title page to The Works of Lucian (1780), translated by Thomas Francklin — Source.

Lucian of Samosata, who lived from ca. AD 125 to ca. AD 200, was an Assyrian writer and satirist who today is perhaps best remembered for his Vera Historia, or A True Story — a fantastical tale which not only has the distinction of being one of the first science fiction stories ever written, but also is a contender for one of the first novels.

A True Story is a stylish and brilliantly conceived work of the imagination, and readers may still delight in its descriptions of lunar life forms and interplanetary warfare, its islands of cheese and rivers of wine, and its modernistic use of celebrity cameos. But by the time of its writing, Lucian was already several years into a period of literary adventurism that had brought him considerable fame — and infamy — as one of the sharpest, funniest, and most original comic writers of the age. With the quartet of works consisting of Dialogues of the Courtesans, Dialogues of the Dead, Dialogues of the Gods, and Dialogues of the Sea-Gods, Lucian would not only scandalise some of the most influential and celebrated figures of the empire, but in what is perhaps the best known of these, Dialogues of the Gods, he would also furnish the permanent decline of belief in the gods themselves.

In Dialogues of the Gods Lucian conjures a series of short comic scenes in which we find the Greek gods domesticated. Here is Zeus, bluff and irritable, squabbling with Hera over his latest infidelity; there is Aphrodite, reprimanding Eros for making an old lady fall madly in love with a teenager. In Apollo & Dionysus, the adolescent god of wine frets about the over-endowed Priapus’ “growing” interest in him; in Pan & Hermes, Hermes tries to duck the issue of his paternity — “how should I come by a son with horns, and with such a shaggy beard and cloven feet, and a tail at his rump?” — until, that is, Pan tells him about the harem of nymphs he keeps in Arcadia. “Indeed. . . well — son — come hither and embrace me!”

With these twenty-six peeks behind the curtain of the great Hesiodic myths, Lucian draws up a sensational image of Heaven and the legends of its tenants, variously recasting them as impotent, venal, needy, irresponsible, opportunistic, sex-obsessed, and power-mad — hardly immaculate, but just like those made in their image, permanently insecure and just as prone to lowering thoughts and deeds.

A Gathering of the Gods in the Clouds by Cornelius van Poelenburgh, ca. 1630 — Source.

These “closet dramas” would deliver a stinging blow to Greek polytheism. While philosophy was now the religion of state for Athenians, the ancient beliefs, so obviously rural in origin, were undergoing a minor resurgence in popularity. For Lucian this was intolerable. As one of the most gifted and popular satirists of his time, at the peak of his powers, and having just survived an attempt on his life by a gang of religious zealots, the gods of his forebears were ripe for his attentions.

Born in Samosata on the banks of the Euphrates in Assyria, Lucian lived for the early part of his life under the Roman emperor Hadrian, and then as an adult under Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and Commodus. Because there are no contemporaneous accounts of his life, not much more is known about him other than what little can be gleaned from his collected writings. We know that he spent the early part of his adulthood educating himself as he wandered in and around Ionia, Italy, and Gaul, all the while developing his skills and reputation as a rhetorician. At this he would become successful and quite wealthy, speaking in court on behalf of paying clients, writing speeches for high-standing citizens, and publicly demonstrating his ingenuity with improvised riffs in response to suggestions called out by audiences.

He wrote extensively throughout this period — generally arch, philosophical works, composed in stylish Attic Greek, and drawing on his formidable skills as a rhetorician. Yet in his early forties he seems to have suffered what we would now call a midlife crisis — or at least, a crisis of conscience. As Henry Fowler puts it in his introduction to The Works of Lucian of Samosata, “Rhetoric had been left to the legal persons whose object is not truth but victory.” This idea would certainly become one of the underlying themes of Lucian’s writings, and he learned to despise the self-righteous. But whatever triggered the crisis, he felt sufficiently moved to abandon the respectable life of the rhetorician and relocate permanently to Athens, where he would devote himself completely to the writing and performing of comic satires.

The journey to Athens would prove both eventful and portentous. Along the way, accompanied by his elderly parents, Lucian encountered the fraudulent priest Alexander of Abonoteichus, leader of the newly emerging cult of the snake god Glycon. Alexander claimed that a snake in his possession was the reincarnation of the god Asclepius, and that only he, Alexander, could channel and interpret its divine prophecies. Lucian was simultaneously disgusted by the influence wielded by Alexander and by the credulity of his followers, whom he described in Alexander the Oracle-Monger as having “neither brains nor individuality. . . with only their outward shape to distinguish them from sheep.”

Two statuettes of the snake god Glycon, which Lucian revealed to be merely a snake in a blonde wig, manipulated by the false prophet Alexander — Source.

Having identified the manifestation of the snake god as nothing more than a cleverly manipulated puppet, Lucian was determined to expose the puppet master. The attempt nearly cost him his life. When his turn came to ask Alexander for a prophecy, Lucian’s question was as rash as it was amusing: “When will Alexander’s imposture be detected?” Alexander responded with a characteristically cryptic answer, and then had Lucian followed. Discovering that Lucian was about to make a sea crossing, Alexander paid the captain of the vessel to have Lucian and his family slain and thrown overboard. Only the captain’s last-minute desire to meet his impending retirement with a clean conscience prevented the murder.

Lucian would never forget the experience, and it is to be supposed that it galvanised him, honing his innate sensitivity to duplicity. With the satires that followed he began to dismantle the pillars of hypocrisy wherever he saw them. With Dialogues of the Courtesans, he sketched a merciless portrait of the hetaerae — the high-status prostitutes of Athens — and their puffed-up clients. He built on these with Dialogues of the Dead, in which he ridiculed the vain expectations of a host of recently departed celebrities arriving in the afterlife, including the eminent philosophers Diogenes and Polystratus, the warrior Hannibal, and Kings Philip and Alexander of Macedon. Having dealt with the rich, the famous, and the mighty, he turned his gaze upwards, to the very peaks of Mount Olympus. With Dialogues of the Gods and Dialogues of the Sea-Gods, he would visit his wits on Heaven, and taunt the gods themselves.

It was not always like that. From the middle Renaissance into the late 1800s, Lucian was among the most widely read of the “Greeks” in Europe, largely thanks to the efforts of the great Dutch theologian Erasmus and his English friend Thomas More. Sharing an appreciation for Lucian’s amusing scepticism and the elegance of his prose style, together they produced, in the early 1500s, the first major translation of his works into Latin. The project, which took several years to complete, would become a publishing sensation, going through more than thirty editions in Erasmus’ and More’s lifetimes alone.

Not everyone was pleased to see it. Thanks to the international appeal of the Erasmus-More translations, by 1590 Lucian’s entire canon had been placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Vatican’s catalogue of texts considered to be too salacious for public consumption. Yet despite such prejudices, Lucian’s popularity continued to grow rapidly — not least of all in England, where his dialogues found their way on to school curricula. Thomas Linacre, Thomas More’s old teacher, believed that “Your toil will become light and amusing and your progress sure, if you will only read a little Lucian every day.” And so it proved, as Lucian was endorsed by a new generation of schoolmasters, each in agreement that his sharp wit, broad humour, and matchless style provided the perfect means by which a young lad might be encouraged to attend to his Latin.

A number of English translations soon followed. First was Francis Hickes’ Certaine Select Dialogues of Lucian of 1634, updated and republished in 1664 to include Jasper Mayne’s Part of Lucian made English from the Originall. Ferrand Spence’s more extensive Lucian’s Works of 1684 was the first to make use of vernacular English, a decision which infuriated the esteemed poet and translator John Dryden. In his essay “The Life of Lucian”, which would preface the subsequent four-volume Works of Lucian of 1711, Dryden remarked of Lucian that “No Man is so great a Master of Irony, as our Author” — but of Spence, thought it “not worth my while to rake into the filth of so scandalous a Version. . . he makes [Lucian] speak in the Stile and Language of a Jack-Pudding, not a Master of Eloquence. . . for the fine Raillery, and Attique Salt of Lucian, we find the gross Expressions of Billings-Gate, or More-Fields and Bartholomew Fair.”

For the next sixty years or so, “Dryden’s Lucian”, as it became known, would serve as the standard. Yet as Lucian became ever more popular, and as the demand for new editions grew, so the translations kept coming — and with them a series of alternating editorial visions. John Carr’s Dialogues of Lucian of 1773 succeeded in being vivid, earthy, and companionable, directed as it was towards the general reader rather than the classical scholar. Thomas Francklin’s Works of Lucian of 1780 took a more academic approach, a rebuke to Carr that resulted in a more respectable, but considerably less fun, translation. William Tooke’s Lucian of Samosata of 1820 might be thought of as a “Goldilocks” edition — pitched just right, with Tooke allowing Lucian’s schoolboy humour, his sly philosophy, and his elegant prose to shine through just as he found it in the Greek, untroubled by any notions of incongruity.

Detail from the title page to the 1774 edition of Carr’s Dialogues of Lucian — Source.

Yet as the eighteenth century drew to a close, Lucian slowly began to fall out of favour. Victorian attitudes towards propriety prevailed, and schoolboys had their Lucian substituted with Ovid, Horace, and Virgil. The story might have ended there, had relief not come from the unlikeliest of places — a small tomato plantation on the island of Guernsey.

By 1903, at the age of forty-two, Henry Fowler found himself at a low ebb. Behind him lay an undistinguished academic career at Balliol College, Oxford; this was followed by ungratifying and only moderately successful employment as a schoolmaster, and then occasional freelance work as an essayist for Punch and The Spectator. His brother Frank, twelve years his junior, had found himself similarly disappointed: he had graduated with a third-class degree from Cambridge, and was now making plans to farm tomatoes in the Channel Islands.

Despite their relative lack of academic achievement, the two brothers were altogether devoted to the Greek and Roman classics, and shared a great passion for, and facility with, language. Throughout Henry’s time as a schoolmaster, teaching both Latin and Greek first at Fettes in Edinburgh, and then at Sedburgh in Yorkshire, he would visit Frank during the holidays at his rooms in Cambridge. There they would talk enthusiastically about their plans to one day write together.

There were a number of good reasons for choosing Lucian. First, the most recent translation, a concise edition compiled by the Cambridge scholar Howard Williams in 1888, was not only out of print but considered to be unsatisfactory by the Fowlers. Second, they felt that the great satirist had been neglected for too many years, having slowly fallen out of fashion, and that a mass-market revival was due. Third, Henry had learned that Oxford University had recently begun publishing a series of translations of Greek and Roman classics under the Clarendon Press imprint, and felt that a complete Lucian would make an ideal addition to the catalogue.

But there was also another, more carefully concealed reason: Henry saw some interesting parallels between his own lack of religious faith and Lucian’s questioning of the religious authorities of his day. Henry had little time for religion and the “airs of intellectual superiority” he felt it engendered. As Jenny McMorris quotes in her excellent biography of Henry, The Warden of English (Oxford University Press, 2001), “Thirty years ago I thought religious belief true; twenty years ago doubtful; ten years ago false; and now it is (for me, of course) merely absurd.” It is doubtful that Henry shared any of this with his publishers when he pitched the idea of a new edition. He was canny enough to sense that it would not only prove an unhelpful confidence, but that there were enough good reasons to persuade Oxford to fund the book’s publication anyway without invoking dangerous personal ones.

The commission to translate Lucian agreed upon, Henry and Frank divided the Lucian workload between them. The pieces which Henry translated are marked in the books with an “H”; Frank’s with an “F”. Those translations they found more challenging, and on which they thus found it necessary to collaborate, were marked “H. F.” By this method they were, by the close of 1904, able to present to Oxford their complete works of Lucian.

Well — not the complete works. During their initial proposal to Oxford, Henry had noted that several of the dialogues might need to be expunged so as not to offend the decency of their readership (who were not, after all, only scholars or students, but also more general readers). Not wishing to pre-empt which pieces would be acceptable to Oxford and which not, the Fowlers willingly handed over the job of censor to the university Vice-Chancellor William Walter Merry. On this occasion at least Merry was quite liberal with his blue pencil. In Dialogues of the Gods alone he excised seven of the twenty-six.

Of these, Zeus & Ganymede and Hera & Zeus would have been the most obviously problematic for Merry. In the first of these, Lucian sets the familiar mythological scene in which Zeus takes on the appearance of an eagle so that he may swoop down on the comely shepherd-boy Ganymede and carry him up to heaven forever. “Kiss me, you fine little fellow!” says Zeus on their arrival. “You are now an inmate of Heaven. Instead of milk and cheese you will eat ambrosia and drink nectar.” Ganymede is understandably distraught. “But where am I to sleep at night?” he asks innocently — to which Zeus replies, “Little numbskull, I brought you away that you may sleep with me!”

The Abduction of Ganymede by Peter Paul Rubens, ca. 1611. Artists would treat the image of Ganymede quite differently according to their own visions of this mythical moment. In Rubens’ painting he is a comely youth on the verge of adulthood; in Rembrandt’s 1635 interpretation he is a wailing toddler — Source.

In Hera & Zeus, Zeus tries to justify the presence of his new erômenos to his furious wife. She is having none of it. “Zeus! I hope never to proceed so far in condescension as to let my lips be contaminated by a Phrygian shepherd-boy—and such an effeminate stripling too!” To which Zeus replies, “Mind your language, madam — this effeminate stripling, this Phrygian shepherd-boy, this delicate youth. . . Ah, goodness, I had best say no more, lest I overheat myself!”

Four of the remaining five dialogues on the blacklist are not nearly so contentious, though one can still see why Merry might have been nervous about allowing their inclusion. Hermes & Helios is a bit of racy tittle-tattle in which Zeus sends orders to Helios, the sun god, to stay in for a few days so that he can spend an unnaturally long night copulating with Alcmene. Merry would only have seen fit to censor it due to its bawdiness, a highlight of which is when Helios chunters about how, in his day, “such things did not use to happen. . . Whereas now, for the sake of one graceless woman. . . poor mankind must live miserably in darkness all the while, and — thanks to the amorous temperament of the king of the gods! — there they must sit waiting in that long obscurity, till this great athlete you speak of is finished!”

Detail from The Lovers by Giulio Romano (ca. 1525), thought to show the encounter between Zeus and Alcmene that would result in the birth of Heracles — Source.

Apollo & Hermes is similarly risqué. Here Hermes relates to his companion the story of how Hephaestus has managed, at last, to catch his wife Aphrodite in bed with Ares, the god of war. Trapping them in a magical net like a pair of eels, he calls all the gods to witness the adultery for themselves. Despite this highly embarrassing situation Hermes confides that, even so, “I could not help thinking that Ares, when I beheld him so entangled with the fairest of all the goddesses, was in a very enviable situation.”

In Pan & Hermes, Pan claims Hermes as his father. Again it is easy to see why Merry drew a line through this. Not only is Pan boastful of his many sexual conquests, but there is an uncomfortable moment in which we try to figure out quite how goat-like Hermes was when he made love to Penelope — a touch of bestiality that did not go unnoticed.

Apollo & Dionysus begins with Dionysus raising the seemingly harmless subject of Aphrodite’s variously natured children. However, it soon emerges that this is merely a preamble to an embarrassing tale in which he confesses to having been cornered by Priapus and his giant penis. He is clearly worried about this encounter and what it means but, like a schoolboy wanting to ask a friendly uncle about girls, tries to approach the subject from another angle so as to make his enquiry seem rather more casual, and therefore less excruciating. Regarding Merry’s blue pencil, this one rather speaks for itself.

As to why the seventh, Poseidon & Hermes, was excised is a bit of a mystery. The dialogue deals with the birth of Dionysus from Zeus’ leg. There is nothing in it that is particularly shocking even to delicate sensibilities, and the story of how Dionysus was born would already have been known to anyone with even a casual familiarity with the Greek myths. Perhaps it was the idea that a man might give birth on behalf of a woman that bothered Merry; perhaps it was the passing references to adultery and hermaphroditism — though one imagines that these could easily have been removed without damaging the text too severely. Whatever his reasons, it seems we will never know exactly what he saw in it that so exercised him.

Depiction of the birth of Dionysus from an Apulian vase painting ca. 405–385 BC — Source.

In 1905, the four-volume set The Works of Lucian of Samosata was published to great critical acclaim, and remained in print until 1939. The Fowlers capitalised on their successful partnership the following year with their first bestseller, a book of English usage and grammar they called The King’s English. Frank died in 1918 aged forty-seven from tuberculosis; Henry died in 1933 aged seventy-five, and would be remembered by The Times as “a lexicographical genius” thanks to his work on the first Concise Oxford English Dictionary.

As for Lucian himself, the details surrounding his death remain something of a mystery. The story that he was torn to pieces by dogs is a well-known myth propagated in the tenth century by the compiler of the encyclopedic Suda, a Christian who was unimpressed with Lucian’s perceived mockery of the faith. Lucian was largely, but not entirely, innocent of the accusation: his Death of Peregrinus had made characteristic fun of the newly emerging religion, and it remains one of the few first-hand accounts of its earliest expressions. He saw out his days in Egypt, having been pastured by the emperor Commodus into an easy and well-paid legal post. We know that he performed his dialogues there, and that he suffered badly from gout, an affliction about which — naturally — he wrote a play, featuring the goddess Gout herself. As Henry Fowler writes in his introduction to The Works of Lucian of Samosata, “whether the goddess was appeased by it, or carried him off, we cannot tell.”

Nicholas Jeeves is a designer, writer, and lecturer at Cambridge School of Art. He is also designer and editor of Lucian's Dialogues of the Gods, a new edition of Lucian's comic masterpiece out now on PDR Press.