Vanity of Vanities: Fool’s Cap Map of the World (ca. 1585)

A geographer named Abraham Ortelius produced in 1570 a bound bundle of fifty-three maps. It was the first global atlas, and became a bestseller; Ortelius titled it Theater of the World. A few years later, Jean de Gourmont imposed an “Ortelius projection” — the globe flattened into an oval — onto the visage of a court jester: an imago mundi as feast of fools. And a decade or two after that, an unknown artist made the copperplate engraving featured above, based on its woodcut precursor. The South Pole is where a chin might be, and Borneo near the right cheekbone. This Fool’s Cap Map of the World has become one of the most widely reproduced images from the early modern era, though no one can say precisely what it means. Does the fool represent our world, the vain strivings of its denizens? Or the futility of cartography itself: its presumptions of completeness, the hunt for terra nullius? Perhaps both snickering jesters are present at once.

The quotations plastered across the map mostly concern worldly meaning. We encounter, inscribed left of the cap on a floating cartouche, three responses to life on earth, attributed, respectively, to Democritus of Abdera, Heraclitus of Ephesus, and Epichtonius Cosmopolites. You can “laugh” at its absurdities (deridebat); “weep” over its state (deflebat); or, as with the maker of this map, “portray” its properties (deformabat, a word whose etymology perhaps acknowledges how every cartographic depiction is also a deformation). As our eye roams across the other texts, we find quotations that span the poles of stoicism and pessimism: from “know thyself” to a question that conjures the jester’s cap and bells: “Who does not have donkey’s ears?” Below the map, there’s a line from Ecclesiastes numbering the fools in the world as “infinite”; on the staff, there’s a snippet that echoes Psalm 39: “All things are vanity, by every man living”. And across the fool’s brow, we read: “oh head, worthy of a dose of hellebore”. Hellebore was a medicinal plant associated with purging and thus good for restoring balance to the humors. It was used to treat many things — flatulence, leprosy, sciatica — yet the satirist’s audience would have associated this botanical with insanity. But whose head is diagnosed here exactly? Worldly inhabitants who quest after global knowledge? Or those who peddle it in the form of maps?

At the time this Fool’s Cap was created, maps were gradually becoming a more ubiquitous and useful thing. New maps were being continually drawn and printed, collated and standardized, and integrated into various professions. The wonder and hubris of maps was part of the cultural ether; Montaigne’s Essays are framed as a travelogue of the interior self, and Shakespeare’s characters chide cosmographic ambition. And yet, cartography was still in its infancy. The size of Antarctica and the location of Australia remained unknown to Europeans; the ability to calculate longitude at sea was just decades old. Maps were not yet fully tools of imperialism, or engines of global navigation, or the paper-pushing infrastructure of racism. It’s difficult to conjure a moment when ordinary people might have been leery of maps, when the impulse to map seemed odd, vaguely suspicious — even, as the satirist might suggest, a manifestation of madness. How long ago that was, and how buried. The worries of a jester, however legitimate, were easily ignored. “Vanity of vanities”, he sighs. “All is vanity”.

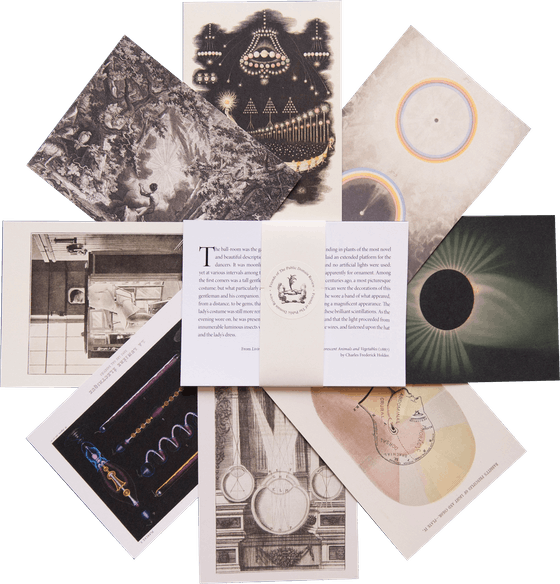

Imagery from this post is featured in

Affinities

our special book of images created to celebrate 10 years of The Public Domain Review.

500+ images – 368 pages

Large format – Hardcover with inset image

Oct 16, 2024